Research Targets Different Life Stages of SWD

After nearly a decade of researching control options for spotted wing drosophila in blueberries, Oregon State University Extension entomologist Vaughn Walton has concluded the industry may be targeting the wrong life stage.

“I personally think that we should change our strategy a little bit,” Walton said.

|

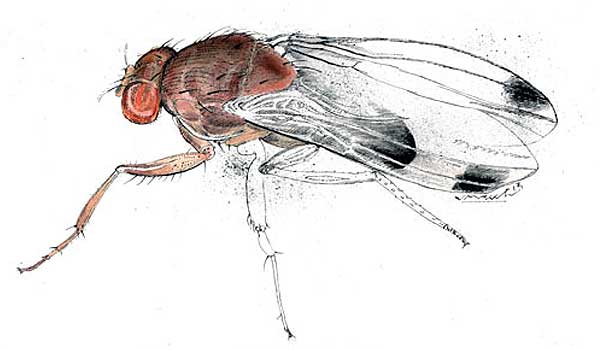

The fly, which first showed up in Oregon in 2011, has dramatically increased production costs up and down the West Coast as growers have increased spray regimes in an attempt to control the pest. Left untreated, the fly, which deposits eggs inside fruit, can cause extensive crop damage – especially to soft-skinned fruit.

To date, growers have concentrated control tactics on the adult stage of the fly. But, Walton said, in looking at the fly’s life stages, adults typically make up less than ten percent of the fly’s population at any one time during a growing season.

“As the season progresses and the fruit starts ripening, we now have a very good idea that the majority of the population is in the egg stage,” Walton said, “so we should try to figure out a way to kill those eggs or at least try to minimize egg laying.”

Making up another “big chunk” of the fly’s in-season population is the larval stage, further complicating efforts to control the pest with sprays targeting adults.

“You can be spraying your compound and not getting control, because those larvae are inside the berry,” he said. “We need to try to take out that portion of the population as well.”

Another fraction is in the pupa stage, he said, leaving less than 10 percent in the adult stage.

“We’ve been spending money on multiple sprays per season trying to get rid of less than ten percent of the whole population,” he said. “I think we as an industry should focus on getting rid of the early life stages.”

To that end, Walton said he has been working with two compounds that may enable growers to shift their SWD control strategies to the early life stages. Both food-grade compounds, the mixtures should fit with organic and conventional systems.

The first approach Walton and his team have been studying involves increasing the skin integrity of blueberries with a product that makes it harder for spotted wing drosophila to penetrate and lay eggs inside the berries with their ovipositor.

Researchers had good results in the lab, Walton said, and then took the product to the field to see if they could duplicate the results. In the field, the product significantly reduced egg laying.

“We put flies on 13 days after application and saw 94 percent reduction in egg laying,” Walton said of the 2017 research.

The second compound that Walton is studying was nearly tossed aside as ineffective after researchers found that when applying it to blueberries, egg laying increased by 77 percent.

“Our first thought was ‘get rid of that,’” he said. “Then we started thinking, if we can actually pull flies away from the fruit with a compound like that, we could lower egg laying in the fruit.”

Further study of different compounds led researchers to the discovery of one mixture that was particularly effective at attracting flies. Researchers formulated that compound into a gum and began testing it in the lab.

“These flies just cannot leave this stuff alone,” Walton said. “They are flying around it. They are mating with each other on it. They are laying their eggs in it. They are feeding on it.”

Researchers then formulated the product into a solid gum and a liquid gum and sprayed it in fields to test its effectiveness in actual production situations. “Over and over we got the same result,” Walton said. “Instead of going to the berries, the flies go to the gum and lay their eggs on the gum.”

Findings of 76 percent reduction in egg laying in fruit were typical, Walton said, and results were the same at each level of the bush.

“Initially we were thinking we were only going to have one compound that we might be able to use in blueberries,” Walton said. “Now we think that these are both products that may be alternatives to pesticides. We are consistently finding 50 percent and higher reduction in egg laying using the first protectant where the fly cannot get its ovipositor into the berry. And we have been able to get the same type of result with the attractant compound.”

The compounds are expected to be available for growers beginning in 2019, when the compound that increases the skin integrity of blueberries is expected to be on the market. The second compound, which attracts egg laying, is expected to be available beginning in 2020. The products will be manufactured and distributed by agribusiness companies, Walton said.

OSU is taking out international patents on both products.

A New Approach to Chemical Control of SWDOSU Extension is analyzing alternative methods for controlling the spotted wing drosophila, but it hasn’t abandoned researching chemical controls. Entomologist Vaughn Walton and graduate student Serhan Mermer, in fact, are taking the unique approach of analyzing the effect of commonly used insecticides on different life stages of SWD. “Previously, people just looked at killing adults,” Walton said. “But about 90 of the population is in these other life stages.” By controlling immatures, growers could significantly reduce the damage this pest inflicts on fruit, he said. And a better understanding of which products work best on different stages could alter how the products are used. What the researchers have found to date is that among Delegate, Spinosad (or Entrust), Exirel and Mustang, Delegate had the most effect on early stages of SWD. Second best was Exirel, Walton said. Going into the research, Walton said he thought Mustang would be most active on the different life stages. But that wasn’t the case. “Mustang Max kills adults really well, but it doesn’t kill the eggs,” Walton said. “Spinetoram (Delegate) shows it kills adults, but it also kills eggs and it kills the first, second and third instars at the highest level (of the other compounds tested),” Walton said. As part of the project, the researchers also are hoping to determine the optimum time to use the different pesticides. Mermer expects to unveil that and the other findings in a paper to be published this fall. The research could have significant ramifications on the use of the four insecticides, Walton said. “For instance,” Walton said, “early in the season when you have mostly adults come in, then you maybe want to look at using one of the compounds that kills mostly adults. Whereas, this time of year (late July), where you are seeing soft berries, the best thing to do is to look at using a compound like spinetoram, because it would take care of those other stages.” Walton added that research to date has shown that using the hardest compounds right out of the gate gives growers the best bang for the buck. “What we have shown is early on, if you have a season with populations increasing, the best strategy is to use the hardest compounds and then back off, because you will get a season-long benefit if you apply some of the hardest, most effective compounds early on,” Walton said. “So, use something like a Mustang early on for the adults, and then use your Entrust or Delegate a little bit later because then you are getting the best benefit on all your life stages,” Walton said. He added that growers need to be rotating chemistries to avoid the buildup of resistance, particularly given the number of sprays going on each season.

|

| FALL 2018

|