Research Looks at European Foulbrood Disease

At the 2022 Oregon Blueberry Field Day, Oregon State University apiculturist Ramesh Sagili provided some preliminary findings of a multi-year research project on the detrimental effects of European foulbrood (EFB) disease on honeybee hives.

|

Oregon State University apiculturist Ramesh Sagili provides Blueberry Field Day participants preliminary findings of a multi-year research project on European foulbrood (EFB) disease on honeybee hives. |

The study, funded by the Oregon Blueberry Commission, is in response to what Sagili said is an unusually high incidence of EFB during blueberry pollination in Oregon of late. Sagili is studying potential factors contributing to the phenomenon, as well as looking into whether a currently available antibiotic treatment is effective.

EFB has been around for many years, Sagili said, but only in the last seven years or so has it been an issue.

“Usually, we will see it in the spring, but we won’t see it after June, but the last seven years, I would say, things have changed slowly,” Sagili said. “Now we are seeing this disease persist to the end of June or even into July.

The disease, which attacks honeybee larvae, is caused by the bacteria Melissococcus plutonius. Affected hives will exhibit brownish larvae that are decomposing.

“Larvae die young, so there are no new bees coming out after a few weeks,” Sagili said. “Colonies become weak and you don’t have good pollination.”

According to existing hypotheses, which Sagili is studying, several factors contribute to the disease, including poor larval nutrition.

“That is a tricky one,” he said of that hypothesis. “It is not like the bees are not feeding the larvae, but it could be that there are not enough pollen resources coming in.”

Sagili said it helps to have additional pollen sources other than blueberries for improving hive health.

“We have seen sometimes when blueberries are there and maple is blooming at the same time, the colonies do okay,” he said. “So, what is in the landscape and surrounding area is important.”

|

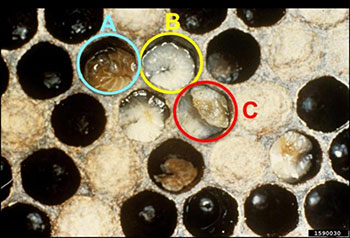

A) Larvae infected with foulbrood; Infected larva (brown) with tracheal system visible through its integument. B) Apparently healthy larvae (pearly white, glistening, C-shaped). C) Curled, discolored larvae, twisting up in the cell.

Credit: Georgia Department of Agriculture, CC BY-NC 3.0 |

In addition, Sagili noted that when nectar is flowing, say from blackberries, which are a major nectar source for bees in the Willamette Valley, bees will switch their foraging dynamics, another factor that can affect larval health.

“What happens if nectar flows start, then the young bees are also recruited to forage,” he said. “But the queen is laying probably 2,000 eggs a day, so there is still a lot of larvae to feed. And that is when the EFB gets bad, because most of the bees are now foraging, and they are ignoring some of the larvae. They are not feeding them in time and in the right amount that they need.”

Sagili is also studying whether use of fungicides to control botrytis during blueberry flowering is having an effect on pollinator health. The bottom line there, he said, is there is no conclusive evidence that it does.

“Research from the East Coast didn’t show any problems with (the fungicide) Pristine with larval buildup or the queen health, as well,” he said.

He is continuing looking into the pesticide exposure hypothesis, he said. “We are putting out pollen traps when the bees are in blueberries in this experiment and we are collecting pollen to see what fungicides are coming in.”

A third hypothesis is whether a new EFB variant has escalated issues with the disease.

“Maybe there is a mutation and maybe we are not getting the EFB control with the antibiotic we have, Terramycin,” he said. “That is another thing we are testing.”

Researchers are analyzing this by investigating the EFB bacteria to see if there is any variation in their genetics, he said.

Brood chilling is another potential contributor to increased issues with EFB.

“When blueberries are in bloom, at times it is still cloudy, cold and rainy, so the bees are not able to keep the brood warm if the colonies are small,” he said.

Factors that could be affecting brood chilling include hive splitting, a practice some beekeepers employ after bringing hives up from California after almond pollination.

“When they do this splitting, they may just randomly pick some foragers and some nurse bees and that can create a colony-dynamics problem,” Sagili said. “So, one hive may end up with too many foragers and the other hive may end up with only nurse bees.

“That can impact pollination and it can create brood chilling, as well,” he said.

A fifth hypothesis involves the pH of blueberry pollen.

“This comes from a study done about forty years ago,” he said. “It says that the pH of blueberry pollen might be impacting the larval development in bees because it has acidic pH. But I don’t think there is good evidence of that, because blueberry is not a major source of pollen for bees. When you bring bees into your blueberries, they get less than five percent of their pollen from blueberries. What happens in blueberries is the nectar foragers are doing major pollination, not the pollen foragers.

“So, honeybees will not collect very much pollen but they do collect nectar and nectar foragers get pollen on their body parts, sufficient enough for fruit set,” he said.

Among preliminary findings Sagili unveiled is that colony nutritional status appears to be negatively correlated to EFB incidence and intensity.

“If a colony has good nutritional status, then probably they have less incidence of this disease,” he said.

He added that there is ample anecdotal evidence that if honey bees have access to other resources besides just blueberries during bloom, they have better nutritional status. “We see less of a problem with EFB in those hives,” he said.

And, he said, research is showing that Terramycin appears to still be effective in controlling EFB.

Sagili said to expect more results next year.