‘Mini Blues’ –

Researching Ways to Grow This Great-Tasting, Small-Fruited Blueberry Economically

Bernadine Strik, Professor and Senior Faculty, Oregon State University Amanda Vance, Research Assistant I, Oregon State University

Chad Finn, USDA-ARS Research Geneticist, HCRU, Corvallis

A new small-fruited blueberry ‘Mini Blues’ was released by the USDA-ARS and Oregon State University Cooperative Breeding Program in 2016. This new blueberry caught our attention because it produces consistently small fruit (less than 1 gram) with outstanding flavor and sweetness. This makes it well suited for the processing industry for high-quality small-fruit markets.

|

| ‘Mini Blues’ fruit, 2019. Photo. B. Strik |

A small-fruited cultivar like ‘Mini Blues’ cannot be economically harvested by hand, even when plants are young. Furthermore, our experience with pruning mature plants has shown us that this cultivar takes at least 25 percent longer to prune than ‘Duke.’ For these reasons we started a new research trial in 2015 to find ways to minimize labor inputs when establishing and growing ‘Mini Blues.’

Our trial was planted in October 2015. The plants are set at 3 ft in the row with 10 ft between rows, are being drip irrigated and fertigated, have weed mat mulch on raised beds and are trellised. Plants were pruned in winter 2015-2016 and 2016-2017 to remove all flower buds – no crop in the first or second growing seasons. Our goal was to encourage growth in the first two years so they would be as ready as possible for machine harvesting in the third year.

We first started our pruning treatments in winter 2017-2018. Bernadine pruned plants as follows: 1) a “control” where plants were pruned as typical for northern highbush blueberry, including removing low growth, narrowing the crown as needed for machine harvesting, and removing less productive or damaged wood using basal and top pruning cuts; 2) “speed pruning” where low growth hanging on the ground was removed and then one or two older or least productive canes were removed at the crown; 3) “hedging” with only low growth touching the ground removed in winter and plants hedged after harvest in summer 2018; and 4) “no pruning” where low growth touching the ground was removed but no other pruning was done in winter 2017-2018 and 2018-2019. The time required to prune was noted. Plants were harvested using a Littau Harvester in 2018 and 2019. Harvested yield and various fruit losses and berry weight and Brix were recorded.

|

‘Mini Blues’ plants that have not been pruned for two winters. July 17 2019 (fourth growing season). Photo: B. Strik |

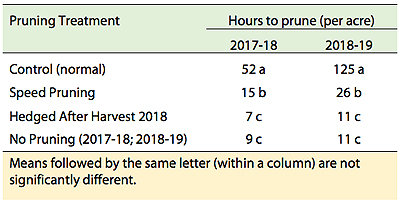

Pruning time. The time to prune the control or normally-pruned treatment was considerable and increased to 125 hours/acre the winter prior to the fourth growing season in 2019 (Table 1). Pruning using the speed method reduced the time needed by 71 percent in 2017-18 and 79 percent in 2018-19. Hedging after harvest did not take much time in 2018 at 7 hours/acre including removal of low growth the prior winter. This treatment was not hedged after harvest in 2019 (see reasons below). While there was some pruning labor to remove low growth in the “no pruning” treatment, this may not be considered necessary by some growers in commercial production. However, machine harvest efficiency may be reduced if low growth was left on the bushes (see below). It is clear that pruning method or leaving bushes unpruned has highly significant effects on reducing labor requirements for this cultivar.

Table 1. Time required to prune ‘Mini Blues’ as affected by treatment

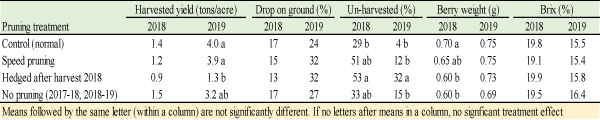

Harvest results. Pruning treatment had no effect on machine-harvested yield in 2018, the third growing season (Table 2). Keep in mind that this was the first season after pruning treatments started (e.g., one winter of no pruning) and the hedging treatment had not yet started. Harvested yield averaged 1.3 tons/acre, but would have been a lot higher if more fruit could have been picked by the machine. Most of the losses (as much as half of total yield remained unharvested) were due to fruit remaining on the bush because it was located below the catcher plates of the machine. This is a negative consequence of starting machine harvesting at a young planting age when bushes are relatively short. There was no treatment effect on ground losses which averaged 16 percent of total yield over the season (Table 2).

In 2019, there was no significant difference in the yield of normally pruned, speed pruned or unpruned bushes with yield averaging 3.7 tons/acre (Table 2). When plants were hedged after harvest in 2018, there was considerable new shoot growth above the hedge point but there was insufficient time left in the growing season for these shoots to set flower buds for next year, leading to very low yield in 2019. For this reason, we did not repeat the hedging treatment after harvest in 2019. Ground losses were not affected by pruning treatment in 2019, but increased compared to the prior year (averaged 29 percent) likely because bushes increased in size. For similar reasons, the percentage of unharvested fruit remaining on the plant decreased (lower proportion below catcher plates). The highest level was found in hedged plants where a large proportion of their total yield was below catcher plate height. There was no significant difference among the other pruning treatments which averaged 10 percent of total yield unharvestable.

Table 2. Effect of pruning treatment on yield, harvest losses, berry weight and Brix of ‘Mini Blues’ in 2018-19.

Berry weight and Brix. Berry weight was significantly greater in the normally pruned bushes compared to the others in 2018, but there was no treatment effect in 2019. Brix was not affected by pruning in either year but was higher in 2018 than in 2019, perhaps due to a cooler fruiting season in 2019 and we harvested three times in 2019 rather than once in 2018 (Table 2).

|

| Machine harvesting an unpruned ‘Mini Blues’ plot July 17 2019 (fourth growing season). Photo: B. Strik |

Observations and summary. In 2018, all treatments could be picked with one pass of the machine harvester, whereas in 2019, three harvests were needed to get all fruit picked. The unpruned and hedged treatments had a longer fruiting season in comparison to the normally pruned control where 64 percent of total yield was picked on the first harvest. ‘Mini Blues’ fruit harvested by machine has had very good quality with a consistent size through the season, very little fruit loss from green or unripe fruit being shaken off the bushes prematurely, no stems on picked fruit, excellent flavor, and high Brix. Fruit loss on the ground and unrecovered fruit were as expected because we are picking relatively young plants where a large proportion of the bush is below catcher plate height, even on these raised beds. We will be monitoring these values as the plants age.

It is expensive to prune this cultivar (high labor hours per acre). Any treatment that reduces pruning cost while maintaining yield and quality is thus a huge benefit for commercial growers. To date, the unpruned treatment looks extremely promising. In most cultivars, pruning reduces yield and increases berry size compared to unpruned plants. However, in ‘Mini Blues’ plants left unpruned for one (2018 harvest) or two winters (2019 harvest), yield was not different than the control. The fruiting season was less concentrated when bushes were left unpruned. However, berry size was only reduced compared to the control in 2018 (0.6 g versus 0.7 grams) and Brix was unaffected. Hedging plants after harvest did not work because new shoots did not have time to set flower buds. We thus do not recommend this treatment for annual fruit production.

|

‘Mini Blues’ fruit on Littau Harvester, first pick 2019. Photo: B. Strik |

Considering the huge labor savings of leaving bushes unpruned and the ability of these plants to maintain yield and berry size over two seasons to date, this treatment looks very promising. We will need to see how long we can go without pruning before plants will need renovation – a hard prune back to encourage new growth, leading to a year without fruit production and a recovery period. Depending on how long unpruned plants can go without major negative consequences to yield and quality, the speed pruning method may end up being a good compromise for sustainable yield. Stay tuned for more results as we continue this study.

Thanks to the Oregon Blueberry Commission for funding and Littau Harvesters Inc., Fall Creek Farm & Nursery and Bird Gard LLC for in-kind support.